The Irish of St. Columban, Quebec

In the province of Leinster, Ireland, in the year 560, Columcille was obsessed with the beauty of his master’s book of psalms. In the dark of night, he secretly copied it. A monk, he was also a capable warrior, once named Crimthann, the Fox. When he was forced to give up his copy, his injury festered, contributing to an act of revenge for the death of one of his followers. His revenge left him victorious and in possession of his copy of the psalms, but he was still a monk, and the Church exiled him, setting him to the task of converting 3001 souls to Christianity in penance for those he had killed.

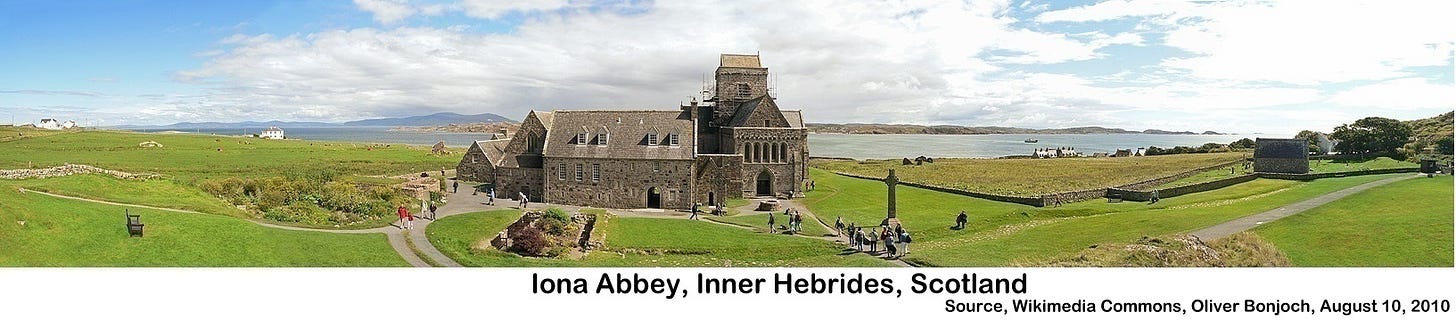

Today, he is known as St. Columba, from the Latin for dove, the Irish monk who set the pattern for the Irish monastic tradition that brought writing back to Western Europe after the fall of Rome. The abbey structure that he established in Iona in the Scottish Hebrides included simple huts for the monks, a dining hall, a kitchen, a scriptorium for transcribing documents, a library, and the fundamentals of a good farm.

In 406 AD, the Rhine River had frozen solid. The Rhine and the Danube had always kept the eastern tribes out of the Roman Empire, but that winter the Rhine ceased to be a barrier to the Vandals, allowing them to establish a permanent beachhead on their far shore. Thereafter, barbarian hordes poured west destroying the very fabric of Roman society. While the Church hierarchy withstood the onslaught, most of the written culture was lost. The tireless monks of St. Columba created abbeys and diligently transcribed and preserved the old documents that had remained out of reach in Ireland. They spread their copies throughout their network during the Dark Ages. In the process, they had a huge impact on all aspects of European life.

Father Patrick Phelan, a Gentleman of the Order of St. Sulpice, was born in that same Irish province, Leinster, in 1795. While his family moved to Boston, his vocation took him to the Grand Seminary in Montreal. His ordination to the priesthood coincided with the arrival of a first wave of Irish immigrants, and the Bishop of Montreal encouraged him to join the Sulpicians in order to minister to these new, impoverished arrivals.

The Sulpicians, who supported a vision that had resulted in the creation of Montreal, owned a seigneury north of Laval, centred in Oka. Like St. Columban, they were an order of brothers and priests. They ministered to the needy in the name of the Holy Roman Catholic Church.

Father Phelan would have known about his Leinster predecessors, and about St. Jerome, among the earliest of monks, and St. Scholastica, the soul sister of St. Benedict. He encouraged his Irish immigrants to colonize the territory in the northeast of the Sulpician seigneury and he founded their parish, naming it for his spiritual forebear.

As early as 1825, there were 250 people in the homestead, and others not far away in St. Jerome. The success of a settlement of Irish Catholics was dependent upon a strong parish priest, but in the beginning, they had not even a chapel, traveling to St. Scholastique when they must. This lack was mitigated by the erection of a cross, allowing them to go to it and pray when time did not permit the longer overland trip to the nearest church. Well after their first chapel was finally built in 1831, at the location of the cross, the early settlers continued to refer to a trip to the chapel as ‘going to The Cross’.

Their first priest, Father Blythe, moved on to become the first priest of St. Jerome, and St. Columban’s second lasted only two years, but the third, Father John Falvey, arrived in 1840 and remained for 45 years. A priest in a small community was much more than a spiritual advisor. He was the person that parties would come to in order to settle differences, draft agreements, register a family event such as a birth, death or marriage or officiate at any community event. He was expected to take the community’s needs to the higher authorities and argue them, and he was also expected to have a business mind, be kind and patient, set an example of generosity and establish proper education for the children. Father Falvey, according to all the records, went beyond expectations.

They had no railway connection, nor even a decent road access, and the soil, like so much of the higher lands of the Laurentians, was thinly spread in crevices in a rocky terrain. Farming, with long, cold winters and hot, dry summers left no surpluses. Seeing what they had to deal with, Falvey encouraged his congregants to build mills on the North River, and they fared better with lumber, boasting five mills.

Father Falvey was assisted in his mission by a woman, the niece of Father Phelan. Sister Mary St. Patrick, born in County Kilkenny, Leinster, Ireland, took her vows at her parents’ home in St. Columban and worked tirelessly for the parish, caring for the sick and teaching at the small school until her death at 77 in 1905.

Descended from the spirit of these missionary pioneers, the Irish of St. Columban also moved away, building different parts of Canada and the United States. They took with them their memories of family gatherings, children playing on grey Laurentian rock, the music, the wagon in a field, horse-drawn and piled high with hay, the northern lights and the quiet of winter. Somewhere in their memories the quilting bees go on, the pump organ plays and the sap is being gathered in the maple grove. Trout fishing, walking to the schoolhouse through familiar shortcuts, they are all far in the past today, but the Irish descendants, the people of St. Columban, return nostalgically, and inevitably end at The Cross, at the church where the cemetery bears witness to their roots.

The Irish have suffered many calamities through history, but they always pick up and start over. It is a tradition older than St. Columba. Some descendants of St. Columban, going to The Cross in 2006, discovered that the tombstones were gone, broken and piled in a discreet location behind the church, confusing the records of the dead. They got together and straightened things up, to honour the ancestors of St. Columban: the Dwyers, the Duffys, the Keyes, the McAndrews and many others for themselves, the Irish descendants of St. Columban, to honour the memory of Father Phelan, and to honour their other Leinster predecessors. Going to the Cross took on a new meaning, with the stones being embedded into walls flanking the cross.

Today it stands as an historic site where you can pay your respects, go to The Cross. Directions are on their website at www.stcolumban-irish.com.

Love this Joe…ah yes, the cross and the church on the highest hill in every village. As a kid it was always a great adventure to hike up to the cross in Ste Agathe with my French Canadian pals. They were always quite serious and quiet when we got there. ….. until we tobogganed down thru the church yard !!! Love the historical threads. ❤️B

It’s a pleasure, but learning where I come from stirs up more than I expected.